Education quality, green technology, and the economic impact of carbon pricing

Carbon pricing is among the the most well known coverage devices staying employed or regarded by governments to minimize emissions today. Proponents argue that carbon pricing may well let us to achieve internationally accepted temperature targets at minimal price tag (Borissov et al. 2019, Gollier and Tirole 2015, Rausch et al. 2011).

Even so, most scientific studies propose that carbon taxes will negatively affect output and could be regressive (Grainger and Kolstad 2010, Mathur and Morris 2014, van der Ploeg et al. 2021), although some rising empirical scientific tests obstacle this (e.g. Klenert and Hepburn 2018, Metcalf and Inventory 2020, Shapiro 2021). Mitigating variables that can lower output losses or cut down rising inequality have been given substantial attention in the literature, specifically the system for redistributing carbon-tax income.

What has acquired a lot less consideration is the mitigating job of procedures that promote education and learning excellent. Far better high quality education has the possible to (1) improve the provide competencies necessary to enable eco-friendly technological innovation in response to carbon pricing, major to decrease output losses and increased reductions in carbon emissions and (2) lessen inequality resulting from carbon pricing by making certain that ‘green’ skill acquisition is obtainable to all.

Emerging investigate indicates that green technological modify relies on human funds. For example, the role of instruction and expert labour for the transition to environmentally friendly development in the report of the Fee on Carbon Pricing (Stiglitz et al. 2017) clarifies that creation using thoroughly clean technologies is human capital-intense so schooling decisions develop into carefully interlinked with the energy transition (Yao et al. 2020). At the very same time, shortages of experienced labour may possibly constrain the decarbonisation method of an overall economy (OECD 2017). Human cash has also been connected to firms far better adapting to weather change and environmental restrictions (Lan and Munro 2013, Pargal and Wheeler 1996).

Carbon pricing – by way of its impression on human-cash accumulation – may possibly not only be the cornerstone of local weather coverage but may also act as a enhancement coverage, fostering technological know-how switches and training of the labour pressure. Having said that, if eco-friendly technological change depends on increased-skilled workers and, as a consequence, is talent-biased, then the increased demand from customers for greater-qualified labour ensuing from carbon taxes may well more widen the earnings hole concerning high- and low-skilled personnel.

In a modern paper (Macdonald and Patrinos 2021), we consider how education and learning quality interacts with carbon pricing’s outcome on emissions, output, and wage inequality. Training excellent – as a determinant of the elasticity of skill source in the economy – may act as a mitigating variable each for the influence of carbon pricing on emissions reduction and on economic results, including wage inequality and output.

This argument is parallel to skills and automation: if automation enhances better-expert workers’ productivity, then the elasticity of ability source – for example, by way of the top quality of schooling – boosts the financial positive aspects of automation and mitigates its expenditures (Bentaouet Kattan et al. 2020).

We exam the speculation that cognitive techniques, as an indicator of general human money, are linked with a reduced reliance on emissions in mixture production technological know-how and estimate the subsequent mitigating effect of training high-quality on carbon pricing’s effectiveness and economic consequences, which include wage inequality.

Making use of details on workers’ cognitive techniques and their industry’s emissions for 21 European nations around the world, we find that cognitive techniques are involved with reduced emissions per output and faster reductions in emissions for every output throughout time. All 3 actions of cognitive skills in the OECD dataset – literacy, numeracy, and trouble-fixing – were being related with reduced emissions per unit of output (see Determine 1). We found this affiliation to be correct inside of nations around the world, controlling for amount of schooling, and largely associated with the cognitive skills of skilled and managerial occupations, which would be most included in innovation and adaption.

Figure 1 Association in between one-conventional-deviation-bigger cognitve abilities of staff members and typical annual expansion costs in industries’ CO2 emissions per unit of benefit-added in share point phrases

Notes: Estimates making use of OECD PIAAC info 2012 merged with EU Emissions Accounts by Industry for 2012 to 2019. Observations are 67,877 personnel in 21 nations around the world for numeracy and literacy capabilities 44,446 personnel and 17 nations for issue-solving skills. Associations approximated working with linear regression products managing for education level, sex, age and fastened results for each individual state.

Source: Macdonald and Partinos 2021.

Variation in the reduction of reliance on emissions across industries and inside countries is probable the final result of technological modify, either through innovation or adaption. The affiliation amongst cognitive expertise and reduction in reliance on emissions by industries is regular with ability-degree as an enabler of innovation or know-how adoption. This is even further supported by the finding that the affiliation amongst expertise and decreased reliance on emissions are predominantly amid managerial and experienced occupations, which are most concerned in innovation and driving technological modify.

These conclusions are also steady with environmentally friendly engineering – which permits generation with less emissions – remaining talent-biased: employees with a higher level of literacy expertise contribute a lot more to decreasing the production function’s reliance on emissions relative to capital.

To comprehend how training high quality can interact with carbon pricing, we estimate a normal equilibrium macroeconomic model for 15 European nations and predict the marginal results of an enhance in the selling price of carbon on output, emissions, and wage inequality – described as variances in wages that young children from wealthy and poorer homes earn when they attain adulthood – to capture inequality of prospect. Applying the OECD PISA info for every nation, we estimate the in general potential of households to purchase cognitive techniques for their kids as perfectly as variations in capacity between richer and poorer homes to get cognitive capabilities. Larger-good quality instruction units are, in our product, equipped to give additional cognitive capabilities for a provided stage of expense in education and learning and can do so a lot more equitably.

Our estimated baseline designs predict that a carbon tax reduces emissions but also negatively affects output, steady with regular macro versions of carbon pricing. A carbon tax also raises wage inequality which, in our design, is a end result of inexperienced technological alter remaining skill-biased and the inequality in talent acquisition among richer and poorer households measured in PISA.

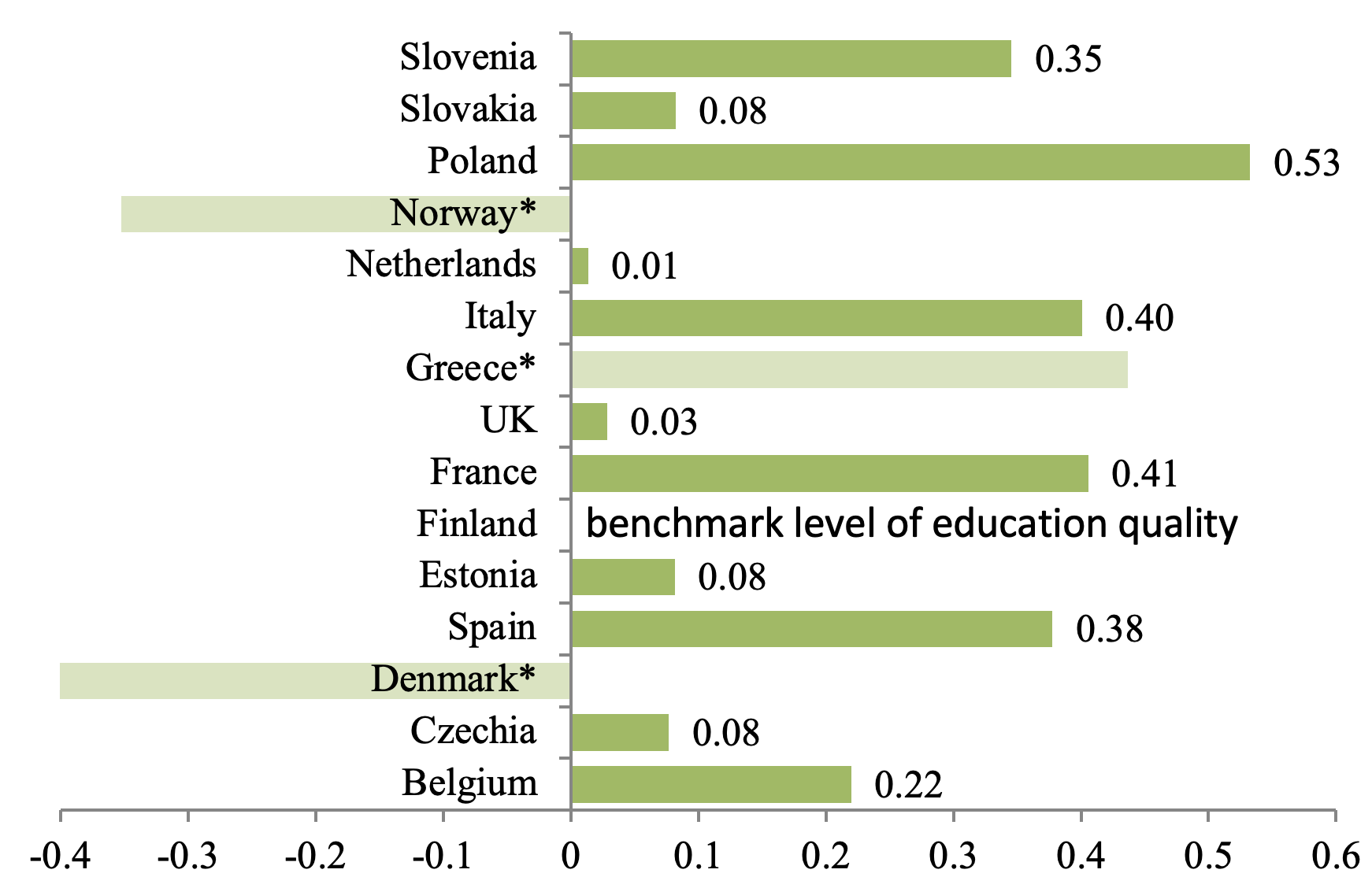

We then examine how the marginal results of a carbon tax for just about every state assess in between the baseline education and learning high-quality routine as calculated in PISA and each individual of two counterfactual schooling excellent regimes. In the 1st counterfactual, we in contrast how the marginal effects of a carbon tax would change if each and every state experienced the identical level of education and learning top quality as Finland – the state with the maximum level of instruction in our estimates. In the 2nd counterfactual, we when compared how the marginal outcomes of a carbon tax would have improved since of variations in the high quality of education and learning measured in PISA across time (see Determine 2).

Figure 2 Projected once-a-year percent of GDP saved in accordance to countries’ existing training top quality (in comparison to Finland’s, as measured in PISA) if a carbon tax have been made use of to cut down emissions by 55{18fa003f91e59da06650ea58ab756635467abbb80a253ef708fe12b10efb8add}

Note: Estimates not statistically important for Denmark, Greece, and Norway. Resource: Linearised projection based mostly on marginal results introduced in Macdonald and Patrinos 2021.

For each simulations, we discovered that enhancements in training excellent (1) strengthened the marginal influence of a carbon tax on lowering emissions, (2) reduced the negative effect on output, and (3) reduced the favourable impact on wage inequality. The magnitude of impact may differ by place dependent, in the 1st state of affairs, on the big difference in education high-quality in between Finland and the country in query and, in the next state of affairs, by how substantially schooling high quality has improved (or declined) throughout time.

By projecting the modifications in the marginal consequences, we can offer a feeling point of view of the impact. For case in point, in the early 2000s, Poland applied a important instruction reform that enhanced its schooling high quality significantly. The reform, which lifted the age of streaming into vocational programmes amongst other coverage variations, had handful of recurrent price tag implications but a big effects on cognitive abilities. In our estimated design, if Poland greater its carbon tax to attain the EU’s carbon reduction targets, the loss in GDP would be a quarter of a per cent less many thanks to the boost in education and learning excellent from the reform.

Our conclusions that cognitive techniques are associated with industries that are a lot more economical in conditions of emissions for each output – and, subsequently, that training excellent performs a mitigating job – is steady with greener technological innovation requiring a higher degree of competencies than present technological innovation. These findings also echo the literature exhibiting that business-degree human capital increases environmental compliance and tactics, and larger education’s affiliation with decreased emissions at the macro degree. Environmentally friendly technological know-how is skill-biased. However, our model does not demonstrate why this would be the case, and the matter justifies further investigation.

Our design could be extended in a number of means in long term research. Initial, labour mobility could be added to understand how the variation in schooling high-quality throughout the EU could affect the impact of carbon pricing. For case in point, nations with lessen-excellent schooling programs could have larger elasticity in ability offer by attracting overseas-properly trained labour however, the existence of very low-high quality training methods inside the EU may perhaps decreased the elasticity of skill provide for the EU as a entire.

A next extension of the product would be to include things like other mitigating things, this sort of as progressive or normally qualified redistribution of a carbon tax, and evaluate the energy of the mitigating result with increased training excellent.

At last, a 3rd extension is to renovate the framework into a advancement model and study regular-state advancement results. This would let us to far better comprehend how the elasticity of skill provide influences carbon pricing’s effects on yearly variations in carbon emissions and other macroeconomic results such as output.

Carbon pricing to cut down emissions that is accompanied by enhancements in training top quality will outcome in improved environmental and financial outcomes. In this context, investing in education and learning high-quality is not to alter the values or behaviours of customers but rather to enable technological adjust that can cut down emissions. Human-money financial investment must enhance cognitive skills and help technological alter to mitigate the expenses and greatly enhance the rewards of enhanced carbon pricing.

References

Borissov, K, A Brausmann and L Bretschger (2019), “Carbon pricing, know-how transition, and ability-dependent development”, European Financial Critique 118: 252–69.

Bentaouet Kattan, R, K Macdonald and H Patrinos (2020), “The role of instruction in mitigating automation’s influence on wage inequality”, Labour 35: 79–104.

Gollier, C, and J Tirole (2015), “Negotiating powerful establishments in opposition to climate change”, Economics of Power and Environmental Policy 4(2): 5–28.

Grainger, C A, and C D Kolstad (2010), “Who pays a rate on carbon?”, Environmental and Source Economics 46(3): 359–76.

Klenert, D, and C Hepburn (2018), “Making carbon pricing operate for citizens”, VoxEU.org, 31 July.

Lan, J, and A Munro (2013), “Environmental compliance and human capital: proof from Chinese industrial firms”, Source and Power Economics 35(4): 534–57.

Macdonald, K, and H Patrinos (2021), “Education top quality, eco-friendly technologies, and the financial influence of carbon pricing”, Coverage Research Performing Paper No. 9808, Earth Bank.

Mathur, A, and A C Morris (2014), “Distributional outcomes of a carbon tax in broader US fiscal reform”, Vitality Plan 66: 326–34.

Metcalf, G E, and J H Stock (2020), “Measuring the macroeconomic affect of carbon taxes”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 101–106.

OECD (2017), Boosting skills for greener careers in Flanders, OECD.

Pargal, S, and D Wheeler (1996), “Informal regulation of industrial pollution in producing countries: Proof from Indonesia”, Journal of Political Economic system 104(6): 1314–27.

Rausch, S, G Metcalf and J Reilly (2011), “Distributional impacts of carbon pricing: A normal equilibrium technique with micro facts for households”, VoxEU.org, 10 June.

Shapiro, J (2021), “Pollution developments and US environmental coverage: Classes from the past fifty percent century”, VoxEU.org, 2 December.

Stiglitz, J E, N Stern, M Duan, O Edenhofer, G Giraud, G M Heal, E L La Rovere, A Morris, E Moyer, M Pangestu and P R Shukla (2017), Report of the Substantial-Amount Fee on Carbon Selling prices, Planet Bank.

van der Ploeg, R, A Rezai and M Tovar (2021), “Carbon tax recycling and common aid in Germany,” VoxEU.org, 2 November.

Yao, Y, K Ivanovski, J Inekwe and R Smyth (2020), “Human money and CO2 emissions in the very long run”, Power Economics 91.